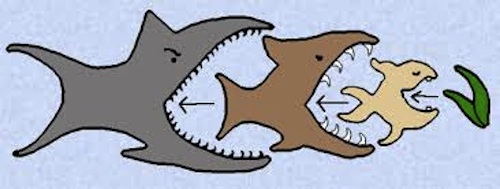

There’s a lot going on right now with orcas (killer whales), almost none of it very good. (“Nature gets revenge on man.”) Here’s some moderately good news for the species, I suppose: they’re now, officially, all the way at the top of the food chain, up there with polar bears. The true focus of the study was to determine where humans rank on the food chain — that had never been done before — using trophic level (basic summary: plants have a trophic level of “1,” meaning they are base-level producers; it goes up from there, so rabbits exist in the second trophic level, foxes in the third, etc; at the top are apex predators, of which the orca is one). Interestingly, humans only have a trophic level of 2.2, mostly because we eat both plants and herbivores. A fox is technically above us on the trophic chain, because foxes just eat herbivores. That isn’t to say that a fox could kill and eat a human — that’s where it can start to get confusing — but technically, their trophic level is higher than humans. Orcas are around 4.5-4.6. Oddly, considering much of what humans eat, they occupy the same trophic level as pigs. Essentially, it breaks down to this: because humans have a varied diet, they occupy a middle trophic level, despite technology; so while a human could kill an orca or a polar bear based on that technology, technically speaking, the trophic level of those animals is almost double that of humans.

Here’s another interesting thing from the survey: for much of history, we’ve been closer to herbivore than carnivore; that’s starting to shift. Since 1985, and more broadly with the industrialization of Asian countries, the world is starting to shift to more of a carnivorous base. The average is still around 80 percent of daily calories coming from fruits, vegetables and grains world-wide (remember: rice is essentially the most important crop in the world), with the remaining 20 coming from poultry and fish — although those latter numbers are trending up.

This all leads to a pretty basic question: can global food supply keep up with (a) increasing population and (b) changing tastes and more appreciation of meat in countries where that wasn’t previously the norm? There are different takes on this all over the Internet and the research world, ranging from The Atlantic (essentially, we need to know trends) to National Geographic to Food Navigator. The last article is fairly interesting and summative; it talks about the need for “novel proteins” to feed animals, i.e. things that aren’t currently used as animal feed.

Consider this, just basically: right now there’s about 7 billion people on Earth; 870 million suffered from chronic malnourishment from 2010-2012. That’s 1 in 8. With 9 billion people on the planet — projections for 2050 — and with India/China eating more protein, that number could rise to 1 in 6. Those 6 won’t necessarily be in highly-industralized nations, i.e. the United States, so the shift will be more dramatic in the poorest areas of the globe. It’s kind of a complicated mess to think about: how do we feed 9 billion people? There are some answers out there, or at least people thinking about it: here, here, here and here. Plus, people are now saying that breadfruit may be the next great superfood to help with world hunger.

Regarding the food chain discussion that started this post, Vice has an interesting take:

Beyond the actual content of the paper itself, there is the whiff of something else going on, only touched upon briefly by other outlets: this challenges our very important self-perception as creatures ruling the food chain. Any vegetarian can tell you that one of the top ten responses to describing one’s own aversion to meat includes some variation of the statement, “Well, humans are at the top of the food chain so I’ll eat what I want” or “We didn’t get to the top of the food chain by eating salad!”

There is a lot of anthropocentrism in the world, yes. It influences decisions about how we chose what to eat, to some extent, and it still does today. There was a good article about that — the choice of what we eat — in this year’s Food Issue of The New Yorker, but I think it’s subscription-only.

This Smithsonian post — their blogs are excellent — on the food chain issue raises a couple of new and interesting points:

The basic trend, in other words, is that as people become wealthier, they eat more meat and fewer vegetable products.

That has translated to massive increases in meat consumption in many developing countries, including China, India, Brazil and South Africa. It also explains why meat consumption has leveled off in the world’s richest countries, as gains in wealth leveled off as well. Interestingly, these trends in meat consumption also correlate with observed and projected trends in trash production—data indicate that more wealth means more meat consumption and more garbage.

But the environmental impacts of eating meat go far beyond the trash thrown away afterward. Because of the quantities of water used, the greenhouse gases emitted and the pollution generated during the meat production process, it’s not a big leap to speculate that the transition of huge proportions of the world’s population from a plant-based diet to a meat-centric one could have dire consequences for the environment.

Alright, now I’m depressed. I started out thinking it was interesting that humans and pigs occupy the same trophic level and somehow I got to these broader ideas about feeding 9 billion people and what an increase in meat-centric diets means for the environment. Here’s what I’ve come to realize in the course of this post: eating is obviously essential to humans, and holds a tremendous emotional role as well. Consider this: my mother just gave me a recipe for pot roast for Christmas. It’s nothing amazingly special — it’s just a recipe for pot roast, on face — but it comes from her mother (long deceased), and her father (deceased)’s mother (deceased), so it involves generations, all passed. When she cooks it, it harkens back to memories of them: what they did when they made it, etc. Food and eating is one of the major connections we have to some of the most important people in our life — and, oh, the base thing we’re doing we need to do to live. So everything flows outward from food, and everything ties back to it. Kinda deep-sounding in a way, but also true. How we feed our people, how we feed our animals, how we feed our poor, and how we deal with the off-shoots of food production (inputs and outputs) are all essential issues for our society. I hope we’re ready.

In the meantime, I’m back to this:

And yes, the original NPR headline that got me down this rabbit (second trophic level!) hole is pretty funny:

https://twitter.com/heideland/status/409690424425467904

One Comment

Comments are closed.