A couple of weeks ago, I was on this “business trip” (quotes indicate that it was for work, but admittedly a part-time job) and struck up a conversation with a couple of seemingly like-minded individuals at a hotel bar on Saturday evening (the bar didn’t have any tap beer, which was rough). Here was the jumping off point: a girl in the discussion had recently taken a job with an idealistic-sounding, education-focused non-profit. Their goal was to fix education, or solve education, or whatever the tag line/mission statement read. She was a former ELA (English Language Arts) teacher and had grown a little tired of the classroom (happens to many), so was looking for a new opportunity and saw this as a chance to be “on the front lines.” (This is somewhat misguided, because “the front lines” of teaching is, in fact, the classroom.) Regardless, she started the job and it was good for a couple of weeks, but then it became (in her words) “a lot of stuff with PDFs and Google Documents and scanning and keeping track of stuff.” In other words, something she had hoped would be transformative became transactional. This happens in a ton of jobs, all over the world, literally every minute. Some studies believe nearly half the workforce is ultimately overqualified for their job. Brief personal interlude before I continue: I’m a grad student right now (but basically done with the degree), and I’m looking for work. I’ve been doing this for a while (seems like forever) and still have nothing; at some point, probably within the next 60-75 days, I’m just going to need a job. Am I going to end up taking a job that I’m over-qualified for? Probably. In fact, I’d say more than likely this might happen. Rubber eventually does meet road on these things, and you need a paycheck to live in a capitalist society. Them’s the breaks. I digress.

In this hotel bar conversation, another person — who was more inebriated than the girl telling the original story — chimed in and was rather loud. Almost violent-sounding. “This is bullshit,” he began, and I braced myself for a potential confrontation here. “Your job is what you (expletive) do. It’s not what you think you do or tell your friends you do. It’s actually what you do.” I thought about this for a while as the two started arguing. First off, it’s a depressing reality of social existence that when you meet new people, one of the first questions is often around their vocation. We do care “what people do,” and as a result, people need a narrative around that. You can’t say “I code PDFs for financial purposes” because that doesn’t sound right — just like you can’t say you’re not busy (double negative!) — so you create another narrative for these eventual conversations. “I manage finances for a global operations hub.” Got it. But then, over time, do you come to believe that’s what you actually do, even if what you really do is look for six-digit codes and enter them into a program created by SalesForce or AMEX or someone?

Basically, the question is: what’s your job? Is it the ideal someone pitched you and you believed/created for yourself? Is it what you fundamentally do day-to-day? Is it what your job could be? Or is it how you tell others about it?

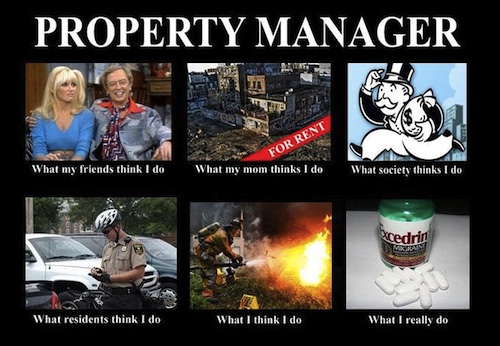

If you believe that work — or your career, in other words — at least partially defines you as a person (which many people do believe), then this is basically a central question. Hell, there’s even a meme about it.

So what do you think: is your job best defined as what you actually sit down (or walk around/stand up) and do, or what it was sold to you as, or what you think it is in your head? And how much of that is based on previous contextual relationships and/or your own need to be defined by the work you do?

How you answer that question says more about your job (and your happiness in it) than what you actually do. Any job can be reduced to a series of simple transactions that are seemingly without meaning. I and most of my friends “do” exactly the same thing: we talk, listen (sometimes), push buttons on a machine, and look at a glowing screen. The mechanics are not that much different than a slot machine addict, pawing a button repeatedly and waiting for the flashy lights.

So what is the difference? The easy answer is to change the question and frame it as “what is the impact of what you do?” or “why do you do what you do?” In your bar friend’s case, I would guess the answers would be “not much” and “I don’t know.” Of course this easy fix to the “what do you do?” question is a red-herring. What we are really driving at is “who are you, what is important to you, and are you doing something about it?”

I did not answer your question directly because you are asking something impossible to answer. What you think you do: the idea of it; what you tell people you do: the perception of it; what you actually do: the mechanics of it. What you do is all of those, your own idea (idealism, cynicism, or in between) gives you personal meaning and drive; what you tell people you do drives the public image of your activities; what you actually do are the mechanics of it.

Now in terms of settling for a job, or being over qualified for a job, what does a job have to do with what you actually do? There is nothing stopping any of us from doing something challenging that we are potentially underqualified for while still holding down a silly job. Karl Schwarzschild derived a solution to Einstein’s equations of general relativity that describe black holes while in the trenches in WWI. Or for non-geniuses, there’s the corner store clerk who happens to brew some of the best beer ever tasted.

Reblogged this on Gr8fullsoul.