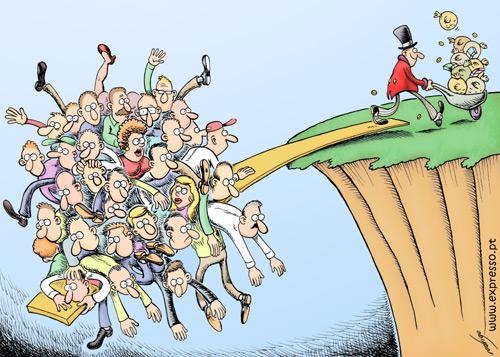

Thomas Piketty got a lot of attention, both good and bad, for his latest book. If you’ve never read it (admittedly, I have not either), the central idea is that, in capitalist economies, wealth will naturally concentrate in the hands of a few people because the return on capital investments typically exceeds standard economic growth. Because visuals are always good, here’s one of the many charts he uses in making his point:

As you can see there, in 1800s France the top 1 percent of inherited wealth had about 19 times more (in terms of multiple of average income) than the top 1 percent of labor earners. That evened out right after WW2, but now we’re going back to a place where the inherited wealth is doubling the earned wealth, essentially. (And that will probably rise.)

Now there’s a new study on “Surnames and Social Mobility in England, 1170-2012”, summarized here, that looks at 28 whole generations of British life and finds that many of the top surnames — Darcy, Percy, Talbot, etc. — have been at the top of that society for roughly the entire time.

The money quote on that paper?

“Social mobility in England in 2012 was little greater than pre-industrial times.”

The spread of universal schooling, the Industrial Revolution, the rise of the social democratic state — none of those things, viewed as large cultural events, actually really changed anything in terms of social mobility and who dominates and concentrates the wealth.

You might stop and think now that the two things referenced above are discussing England and France, and those are different types of societies than the U.S. England has a queen, right? And French people don’t like to work? Isn’t that all right?

Here’s the problem: in the United States, we have our own issues with social mobility. A family in the bottom 90 percent of earners in the U.S. isn’t any richer than they were in 1986; a family in the top 10 percent probably is. People have claimed the U.S. is an oligarchy.

Think about this names study from England for a second. Let’s say Hilary Clinton runs, and wins, in 2016. (Both potentially longshots at some level.) Let’s say she gets two terms. That means that 20 years of American history will belong to Presidents from two families. (4 Bush elder, 8 Bush younger, 8 Clintons.) 20 years isn’t a grand number in the whole lot of things, but still … that’s 20 years between 1988 and 2024. Kind of a sign things are maybe not headed in the right direction?

Lack of social mobility and its eventual even decline is a major issue for the next 1-2 generations and way beyond.

In the United States, I kind of always think the way to look at it is this: if you want to live on a coast and have a relatively decent job, it might be harder to hit the “life milestones” like kids, travel, early retirement, etc. You’re doing more scrapping. If you want to live in seemingly less-desirable places, it might be a little easier to get by. It’s all about the sacrifices you choose to make, because the market isn’t shifting for the needs of one individual or one family (unless that individual has some kind of change-the-world plan).

Reblogged this on Gr8fullsoul.

I think you’re on to a great idea here. I also think the concentration of wealth has alot more to do with world history than just bullying markets. Whats your take on the Rothschild farse of 1877 when Napoleon lost at Waterloo? False news allowed that family to buy up alot of English stocks when they crashed on rumors Napoleon won the war. A lot of wars seem to be created over nothing, similar financiers fund both sides of the equation, and many civilians are fooled to fight for bogus causes. Some hold this as common knowledge, but most do not care because the situation is futile, and a wartime economy is usually more profittable.