This is the first blog post I’ve written in about a week, because I was in Paris and London with my wife for the better part of the last seven days. (I’ll do a recap post on that a little later today, I’d imagine.) Yesterday, we flew back to the United States from Charles de Gaulle (Paris) airport. That flight is slated to be around 9 hours — a little more than going out to Europe — but because of storms in the north Atlantic, we went over Iceland, over Greenland, through part of Canada and down from Minnesota to Texas (so essentially we flew more or less above the I-35 corridor). I’m 6-7, and on the way to Europe I had booked one of those bulkhead seats. I didn’t on the way back (too expensive). So when a 9-hour flight became basically an 11-hour flight, I was somewhat in pain. I needed things to distract me from this pain, and I had a couple of options. I watched most of the Beyonce movie Dreamgirls, and I had a few books to read. Thankfully, I also had some magazines — some of which were provided by the good people at American Airlines themselves, including “The World in 2015” from The Economist. I read through most of “The World in 2015” and, by and large, it was pretty interesting — although they do come out and admit in one article that they tend to get most of their predictions wrong when they do these exercises.

Perhaps the most interesting thing in the entire publication was a little one-page article buried near the middle-to-the-back that spoke volumes about the world’s changing population.

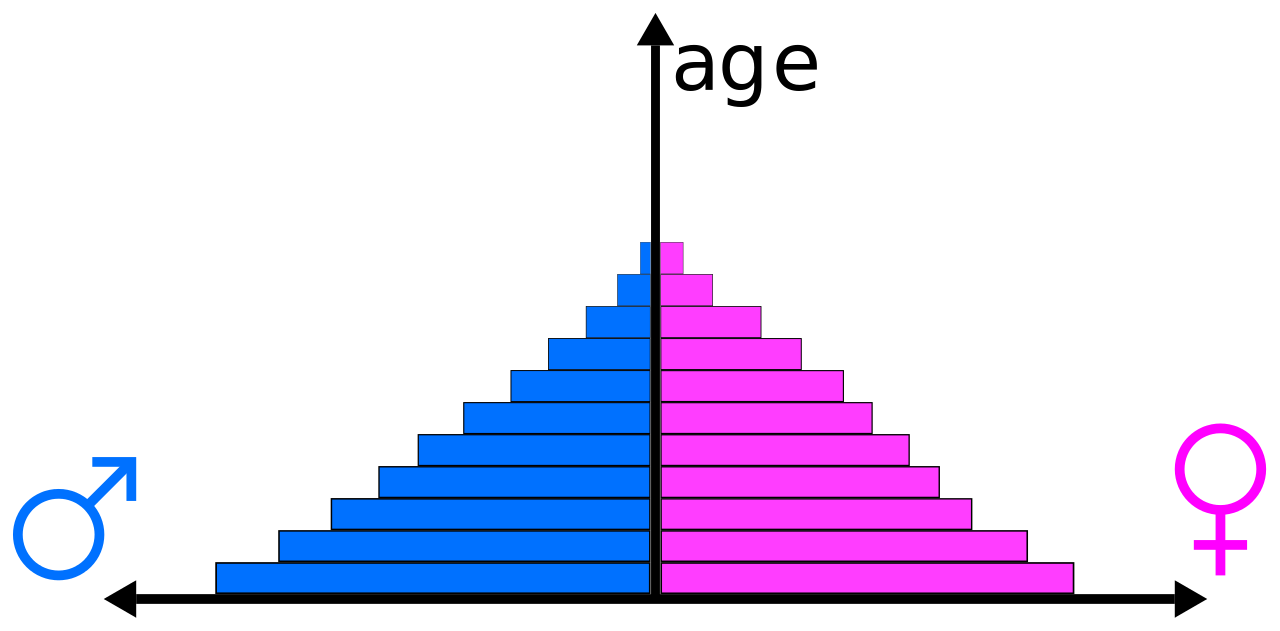

Here’s the article’s link, and here’s the key visual you should look at:

If you look at 1970’s global population breakdown, it looks like a pyramid — youth are the bulk of everything and it gets smaller as you go up (because, uh, well, people die). Because fertility rate dropped from 1970 to 2015, the 2015 chart looks a little bit like a pyramid’s dome. In this case, the biggest is still at the bottom, but equally-big parts are in the 20s/30s period of life.

If you extrapolate all this out to 2060, it’s more like a column — things are almost entirely steady until about 65, and even then, they don’t decrease that drastically.

This has huge implications for how we look at the world. Here it is in the words of The Economist:

For all of history, humans have lived in societies dominated (in numbers at least) by children. By 2060 children will be barely more numerous than any other age group up to 65. And looking after parents and grandparents will be as big a, or a bigger, social requirement as bringing up children and grandchildren. The year 2015 is, roughly, the halfway point in this astounding transformation.

I’ve written a little bit about this before — namely, the idea that perhaps we should be scared by everyone living longer, and/or some similarly-dramatic shifts in ethnic populations within the U.S. alone.

This is kind of nuts to think about, though: we’re one of only a handful of species that even take care of their elderly, and in the span of 90 years from 1970 to 2060, we may shift from a world focused on our children (and caring for them) to a world focused on our elderly (and caring for them). That has huge implications for health, economics, finance, real estate, the future of cities, and pretty much everything else you could think of. What will it all mean?