I don’t feel like spending a huge amount of words on this topic, and it likely would not matter if I did anyway, so let’s start here: While I fully understand the tenets of capitalism and “the free market,” I do still think it’s ridiculous that athletes get paid at their level, or millennials get paid big by brands to make meme videos, and meanwhile teachers and social workers and prison guards (Epstein!) barely make a living wage. I understand the system, but that doesn’t mean the system makes sense.

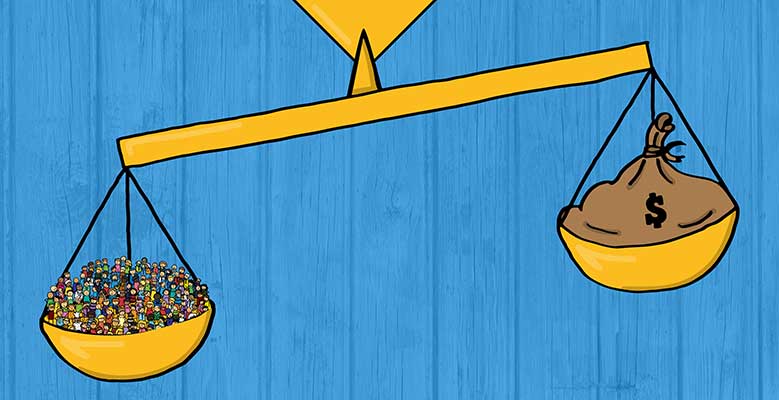

There has been a lot of ink spilled on income inequality and the 1 percent in the past 10 years, and that will only get worse in 2020 with a U.S. Presidential election that potentially will be Elizabeth “War on the Billionaires” Warren vs. an actual (we think) billionaire in Trump. We will see a lot of discussions about money, wealth, taxes, and the like.

Well, here’s some decent new research on income inequality, and let me just take you to an important part:

Our evidence shows that as income inequality in a society rises, the happiness that can be gained from moving up the income distribution increases with it. This can result in people becoming more status conscious and striving to move up the income ladder – and caring less about the growing income inequality around them and its negative effects. Such a shift can be rationalized by believing that income differences are deserved, making income inequality much more acceptable even among those at the bottom of the hierarchy.

So basically, here’s what seems to be happening: We created this little arc where we deify workaholics and we virtue-signal about almost everything. Now add in that lots of people have complicated relationships to money, companies tend to hold all the negotiation cards on salary, many people don’t understand taxation, etc, etc. The list goes on and on.

Where we net out, then, is: “These income differences must be deserved,” and/or something about the evolution of the free market.

That seems to allow us to keep good people, and necessary jobs, down and virtue-signaling, rank-climbing, neck-stepping-on assholes who want more and more for themselves up.

So maybe the core problem of income inequality isn’t anything about taxes or real estate investments or better accountants or whatever … maybe a lot of it simply comes back to virtue-signaling enough that we think these chasms are actually deserved.

Your take?

“These income differences must be deserved,”

Just my two cents. But I’m of the thought this is a cognitive dodge to avoid an uncomfortable truth- our financial standing is a reflection of social worth, not of measured professional capability.

I’ll use myself as an example. At a previous employer I was overpaid compared to my peers and the local market value. Why? Because my boss was a target hitter. He valued two things in workplace life- looking good to his ups , and hitting managerial targets. I hit targets better then anyone else – and didn’t ask questions others did. Now at first blush we could say “Ah, but Luke you worked later hours and hit more targets- ergo you earned more money!”

I’d like to believe that, but realistically I earned more money because I was more valuable to the hierarchy. I made my boss look better in ways my peers didn’t- that’s the real reason I got consistent raises when they didn’t. Good projects they didn’t get. So on and so forth. Working long hours and hitting metrics was incidental to that fact.

Why do firms offer base wages to employees, even if the position is notoriously hard to fill? It’s because said candidate hasn’t proved their worth to the hierarchy yet. Odds are the children and relatives of existing , influential employees get a better offer letter then Joe Blow regardless of Mr Blows qualifications. Again, we return to hierarchy. More influence in the hierarchy translates to more money in someone’s pocket.

On and on it goes, until you have a group of socially advanced & monied people who psychologically convince themselves it was all due to work. If we’re honest, the extra work was correlational at best.

syc·o·phan·cy

/ˈsikəˌfan(t)sē,ˈsikəf(ə)nsē/

noun

obsequious behavior toward someone important in order to gain advantage.

“your fawning sycophancy is nauseating”

A large part of the problem, to add to Luke’s point, is that our hierarchies in business reward sycophancy over knowledge, or skill. This isn’t to say knowledge and skill are irrelevant, those variables are necessary but not sufficient for upward progression. What’s required is something beyond those two variables, which dictates an individual’s place in a hierarchy of authority within the business. What ought to fill that gap, is the variable of leadership – and unfortunately, in most contexts, sycophancy is rewarded over that as well.

A spectrum exists for leadership ability, and not everyone wants to lead; not everyone wants the responsibilities that come with leadership, and that’s a key point. Leadership is a skill-set that fits the problem of diffuse responsibility in a group, and while it’s highly rewarded, it also carries with it equally heightened obligation, as a leader acts as proxy for the responsibility of those beneath in order to aim the efforts of the group. Leadership is tied to duty and obligation, and this balance is good for the hierarchy as a whole.

Sycophancy subverts leadership and derives its benefit from that same niche, wherein serving the interests of the layer of the hierarchy above you, with which you get to directly interact – even at the expense of your own interests, those of your peers, or the hierarchy as a whole – gains you favour with your superior. That sycophancy is repaid with position – almost totally regardless of leadership skill or the understanding of the leadership paradigm, likely as a function of reciprocity (among a handful of other psychological and sociological mechanisms). In this way, the advantage referenced in the definition of sycophancy is achieved.

All that said, balance and a healthy set of hierarchies haven’t been the objectives of business for a very long time. The explicit objective of business in the modern age is imbalance – profit maximization, growth maximization, market share maximization, and too often at the expense of customers, employees, and even future profit. An unbalanced game can also be played in a social sense as well as an in an economic sense. The infiltration of sycophancy into the proper domain of leadership is nothing less than the emergence a sociological Ponzi scheme within a stereotypically economic context.

Leadership and sycophancy will continue to trade-off market share in the space of our hierarchies until we find a way to restrict the clearly unsustainable and costly practices that support the latter. What we need to institute are effective restriction mechanisms that make sociological Ponzi schemes untenable, much as we’ve done for economic Ponzi schemes.

After all, before Ponzi schemes were made illegal in many places, they were just an absolutely brilliant business model that made all the sense in the world for the owners/early adopters of each iteration. A shareholder investing early in a Ponzi scheme is clearly making a very sound business decision by today’s lights.

The unsustainability of a Ponzi scheme is only bad for those not on the winning side of it – the genius of the Ponzi scheme is that those losing are convinced they’re on the winning side – and of course, if you just work really hard on your own Ponzi scheme, you could be a winner too.

The rise of sycophancy is an unfortunate but expected result when a firm forgets what it exists to do.

Ask a random exec and they’ll tell you a company exists to make a profit. Close, but wrong. The objective is to gain or keep a customer by providing a quality good or service. Profit is just the consequence of doing that well.

When the profit metric becomes the objective, strategy dies in a hail of bullets at a gangland tollbooth ambush. You can make a profit any number of infinite ways, none of which need a customer or product. Wells Fargo took this philosophy to its rational (if unethical) conclusion by fraudulently inventing accounts. Shazam, profit!

Don’t need strategy or leadership for that. So people , left with no objective or direction but the pragmatic fact in 2019 they can be left jobless with a phone call, fight over organizational relevance. It then becomes a race to the bottom for the management- people become irrelevant, profit maximizing processes take priority and company resources are spent on infighting between execs and lieutenants. These are firms where sycophancy is a requirement for advancement, loyalty is demanded, and senior managers can’t even tell you what the customer experience is like for their end product or service.

But they can tell you what the profit numbers were last period to the 18th decimal place.