Let’s start with the obvious: No, we are not post-expertise. I watch a ton of true crime, and there’s some couple in The Netherlands who are global experts on blood splatter and get called to trials all over the world about that stuff. That is legitimate expertise. Professors are usually experts in one major thing; I have a friend of a friend who’s (whose?) brother is like the leading global expert on Instagram and teenage female depression. (Hell of a life’s work there, eh?) I know lawyers through friends who are experts at intellectual property casework, which seems like it will be big money for the next 20-25 years, if not longer. So, expertise does exist, for sure. There are pockets of it everywhere in our society.

But on the other side of expertise, there’s a lot of “faux-expertise,” or even “Post-Expertise.” One obvious example is how the Trump administration did some of their appointments. Being appointed to a cabinet post is a lifelong career arc ambition for many; Jared Kushner was legit picking appointees by browsing Amazon book titles. That feels like “Post-Expertise.” As far back as 2015, Americans were distrusting science, which is crazy. There are batshit crazy scientists, sure — but in general the scientific method is something we’ve upheld and vetted for years. Foreign Affairs wrote an article in 2017 about the first world “losing faith in expertise,” and The New York Times has done some book reviews about “ignorance now being a virtue.”

This all touches a lot of different topics: The role of education, keyboard warriors, and, yes, LinkedIn. Let’s actually start there.

LinkedIn and the decline of expertise

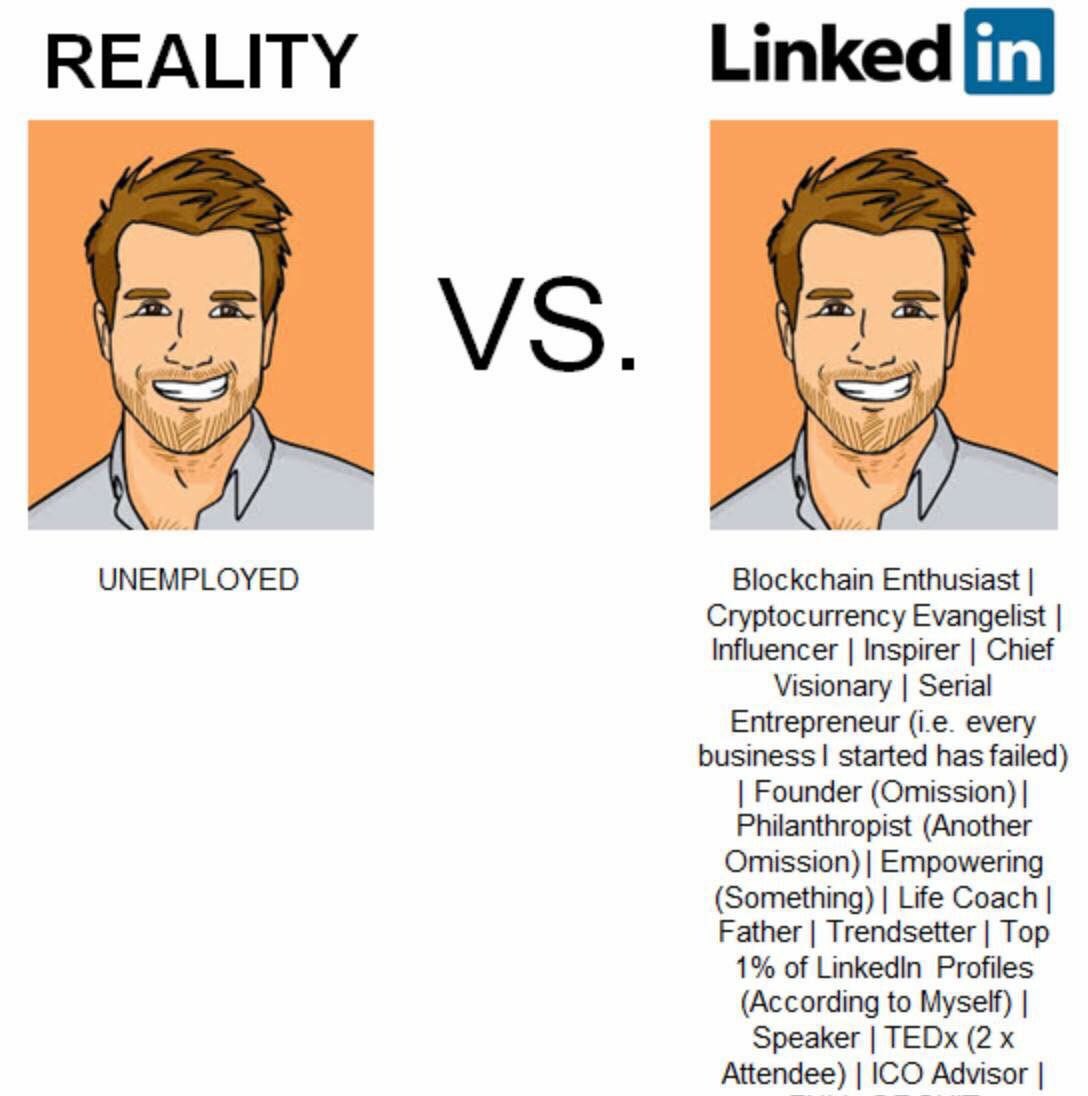

It’s pretty easy to claim to be an expert on something on LinkedIn. Just toss it in your headline. “Thought leader” is a common example, but you’ll see stuff like “Bitcoin Expert,” as typified by this meme:

Now, again, there’s a decent amount to unpack here. Let’s go one-by-one:

- Do people really use LinkedIn? Yes and no. The dirty little secret of LinkedIn is active users, which makes sense. If you’re a big wig at some place or not seeking a job or trying to sell a book, why would you log on LinkedIn often?

- How do people get conned by fake expertise? Because they are lazy, and a lot of people would rather try to contract with what’s staring them in the face than actually do more research. This is also how sales guys sometimes get successful, and/or how dorky 26 year-old guys sometimes get laid.

- The scale didn’t include vetting: Social and digital scaled the ability of people to reach others, but it didn’t scale vetting. If someone says they’re an expert on customer service, a lot of people just believe them on face. In reality, they worked for Amazon for 7 months and got fired, and spun out a “Post-Expertise” career. One is not the same as the other, but the vetting didn’t scale with the profiles emerging.

- How much does expertise matter? For certain roles, it matters tremendously. You don’t want some generalist building your personalization stack, per se. But a lot of jobs are complete bullshit and it’s plug and play. Person A could do it; if they quit or (God forbid) get hit by a bus, Person B can step in and do it. That’s the logic behind job boards too; most of those jobs are plug and play or sales commission jobs, so blasting out worthless emails or targeting the wrong geographic areas doesn’t matter. All it takes is one. If you lose that one, go get another. So in short, expertise matters for some roles, but definitely not for all; it probably doesn’t matter for 75 percent of jobs, to be truthful.

- The Learning Economy: We all want people who can “hit the ground running,” even though that concept doesn’t work as well as we think it does. But let’s say you really need a job and you lie on a resume and say you’re a podcast editing expert. No one vets it, and you get the job. Can you spend a weekend reading and watching stuff about how to edit podcasts and have a decent idea by Monday morning? Sure. So you weren’t an expert, you lied — those are bad things — but there are enough resources out there for us to catch up — that’s a good thing. The problem is that a lot of people who use this “life strategy” don’t actually do the research to make them an expert, and try to “fake it till they make it,” which typically gets you terminated.

That’s some of the stuff tied to LinkedIn and expertise. You also need to remember LinkedIn is broadly a cesspool of virtue-signaling, meaning some guy will post about how he was homeless, had to eat a rat for dinner, and now he is 10x’ing his quarters as a Honeywell sales guy. All you need to do is buy his class or book! A lot of that is bullshit, and buying the class won’t make you successful. That guy was probably successful because he (a) wanted it, (b) needed it, and (c) Honeywell gave him a process to follow. The class won’t help you with A, B, or C. So LinkedIn has scaled the idea of this “Post-Expertise” world, sure, but with some self-awareness, we can realize a lot of that is phony.

What else plays into all this?

Well, Trump, for sure. He broadly treats the Presidency like a business he might sell for scraps down the road, so there’s not a ton of “expertise” in there.

Online forums and keyboard warriors, sure. Scream at people, meme them, call them names, manifesto them, hit them with biased links, no context for debate, etc. Without nuance, it’s hard to develop expertise.

Decline of education, both in the form of us lip-servicing the value of education and us turning higher education into an arms race. Less effective education = less ability to develop expertise.

Temple of Busy stuff too — > it’s more important to be seen as “busy” than “productive” or “expert” at most jobs. And what’s always been funny to me is that even though experts, i.e. subject matter experts, would help a lot in a sales process — prospects usually want to hear from those that know what they are talking about — oftentimes executives “protect” these experts by talking about how busy they are. You want to be busy, or you want to sell widgets? Make a decision, Bob.

Lack of trust plays in here too. Trust is more of a human currency than money, IMHO, but trust in the workplace is not very high, and trust in executive-level ranks is basically in the toilet. If you don’t trust what you’re hearing, how can “expertise” take hold?

Anything I missed, or any takes you have on the decline of expertise over time? Holler.