I wrote a little bit about society being “post-expertise” in August of 2019. Then, this past Sunday morning, I woke up at 4:48am — why God why?!?! — and ended up reading this post from Greg Satell on expertise. This post makes a number of interesting points, so let me start by bullet pointing out some stuff you need to consider.

A few concepts around expertise

- In a 2015 poll, 30% of Republicans and 19% of Democrats supported bombing Agrabah, the fictional hometown of the Disney character Aladdin. In a similar vein, a 2014 poll found that the less people knew about where Ukraine is located on a map, the more they wanted the U.S. to intervene militarily.

- Another study done by researchers at Ohio State University found that when confronted with scientific evidence that conflicted with their pre-existing views, such as the reality of climate change or the safety of vaccines, partisans would not only reject the evidence, but become hostile and question the objectivity of science.

- In fact, in a twenty year study of political experts, Philip Tetlock found that that expert predictions were no better than flipping a coin. Further, he found that pundits who specialized in a particular field tended to perform worse than those whose knowledge was more general.

- Thomas Kuhn explained in The Structure of Scientific Revolutions that, at some point expertise runs its course. As the world changes and evolves, flaws in existing models become more and more evident, eventually becoming untenable. That’s what sets the stage for a paradigm shift. “Failure of existing rules is the prelude to a search for new ones,” he wrote.

- Researchers at Northwestern University analyzed nearly 18 million scientific papers and found that the most highly cited work most often comes from a highly focused team of specialized experts working with an outsider. That combination of deep domain expertise and outside thinking is often what produces major breakthroughs.

OK, let’s unpack

- First thing that pops for me is complexity. It is admirable to try and run systems in a simpler way — that is often a selling point of systems, right? — but it’s impossible. At the human level, people like to over-complicate things because it makes them (the person) more relevant. Can’t ignore that. At the system level, things talk to each other like never before. The financial markets, post-technology, are like billions of lines of code and millions of APIs complex. And that’s your retirement money right there. We’ve gone pretty far away from “simplicity,” and with “complexity” at scale, the idea of “expertise” does become more challenging. That’s true.

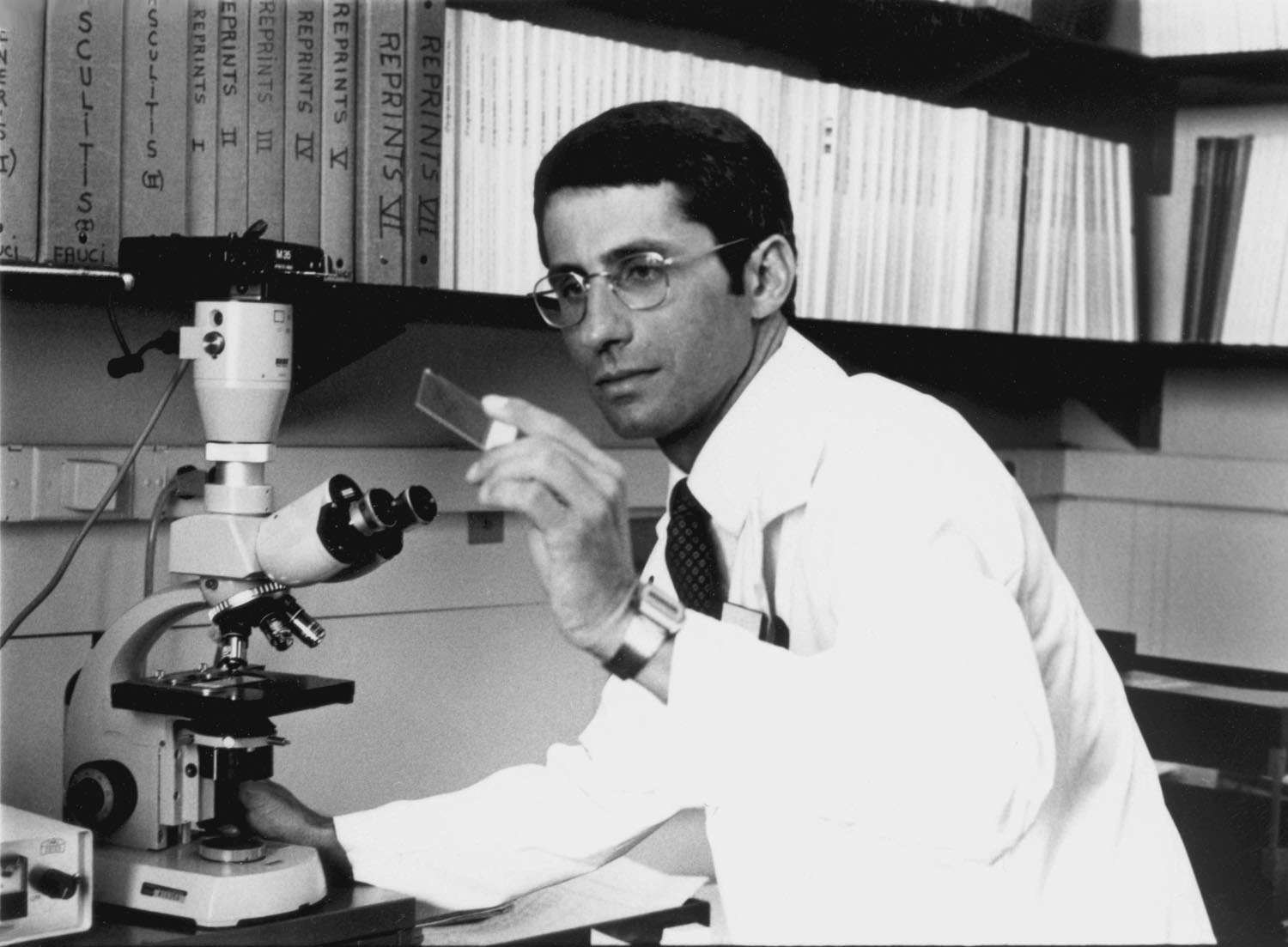

- Partisan bullshit is at a 100-year high, probably: Not an “all-time high,” no, but it’s pretty bad. People love them some confirmation bias, so now you often get in these conversations where a completely well-educated, sensible, seemingly-intelligent and successful person is telling you that Fauci is “part of the Deep State.”

- Leadership cannot discredit expertise, but often do: Trump is a prime example, but business leaders discredit internal experts all the time if the process of discrediting can help them get to market faster, get a better margin, etc. Most of the biggest product problems and PR disasters of the last 10 years came from rushed internal processes that executives nodded at because they wanted to make more money. Can’t ignore that.

- LinkedIn is a problem: Now 600M people globally are suddenly bitcoin experts, whereas in reality 10,000 of those listing the skill are actually bitcoin experts. But because everyone is so slammed and busy, no one takes the time to vet anyone, so you end up hiring some moron for a bitcoin project and it tanks. Down the road, you probably discredit expertise even more.

- Expertise has to evolve over time: Especially because of complexity and because of how “disruptive” so many economic models are.

- That last bullet point is a big deal: I would think, logically, that most of the big breakthroughs of human existence and crisis-solving have come from “a team of experts” + “an outside perspective.” Experts tend to stay in a specific lane. (We are getting into “generalists” vs. “specialists” territory here.) The team of experts needs another perspective, be that a tech person, a “design thinker,” a bitcoin expert, or whoever. If you try to solve The Rona with just disease experts, well, that’s 200+ years of experience (the whole team) of a specific way of thinking. You might need someone to help them break out of that.

So, do we lack respect for expertise?

No, not necessarily and not broadly. I don’t think people call a plumber and then, when the plumber shows up, they ask that person for medical advice. And I don’t think people go to doctor’s offices and bring a plunger, asking the doctor to come back to their spot and snake their toilet.

So, in general, I think people understand the idea of expertise and respect it. Good.

The bad: I think we have a lot of platforms and channels and specific “poles” these days because of the rapid scale of digital and mobile. So, if you want to believe one thing, you can find a way to believe it, you can find data to back that one thing up, etc.

Phrased another way: uh, Facebook.

So while I think we respect expertise broadly, I think we’ve got some issues in how we execute on that nowadays that maybe we didn’t have, say, 60 years ago. (Or had in different forms.)

Your take?

Personally, I view this as the double edge sword of digital technology. On one hand, it has enabled otherwise respected experts who once faced barriers between them and regular folks expand their reach to a worldwide audience. On the other hand, the freeing of these barriers has also lowered the threshold for almost anyone to claim they are an expert (with questionable credentials) and build a sizable audience that ironically solidifies their expertise.