Salt Lake City has already been recognized for having way-above-expectations public transportation, and the Milken Institute called it out as a great place to live and work, but now … it might be the city most representative of the American Dream. This all comes off Harvard’s social mobility report, broken down into a series of charts and graphs (fun with data!) over at The Atlantic. There are some interesting heat maps on that link, but what you really need to know are these two charts.

Essentially, if you measure “absolute upward mobility” — which is how a child’s opportunities compares with those of their parents — then the best cities in the U.S. for “The American Dream” are:

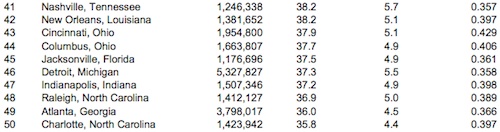

And the worst cities are:

The top 10 makes a lot of sense — SLC has been praised as a great city for over a decade now, and most of the other cities are either university hubs (Pittsburgh, Boston), business centers (NYC, San Francisco), or located in the Northeast corridor somewhere (Newark, Manchester). I live in Minneapolis and can’t fully explain why it always makes these lists. It’s a great city with good Fortune 500 companies, but it’s very hard for an outsider there; the culture is super insular — but maybe that contributes to the absolute upward mobility too (children love, then ultimately surpass, the achievements of their parents).

That bottom 10 is a little confusing, because you have some of the same trends you see in the top 10 — for example, the Raleigh area is a university/research hub and Indianapolis might be the future of the start-up culture, but the broader message seems to be: stay away from the American Southeast if you want to do better than your parents did. That’s odd, because while there are some parts of the SE that often get criticized — say, Mississippi or Arkansas — the cities on this list are some that are considered “the new capital of the American South,” like Charlotte, Atlanta, and the Triangle.

Oddly, Ohio has terrible rates of upward mobility, whereas PA (right next door) fares much better. Texas has high rates — there’s a lot of money in Texas, for sure — whereas the parts of the South/Southwest around it don’t. And then, while most of the individual cities that are good for upward mobility are on the coasts (minus Minneapolis and Pittsburgh, basically), the entire region with the most mobility is the Great Plains (again, this could tie back to oil).

I’m wondering if the generational idea here is that how we achieve more than our parents ties back to money, and oil/gas/energy represents money, as do business ideas — hence the top 10. Some of the bottom 10 are research hubs, which can take longer to become money. Or maybe this is just broadly representative of what happened to American jobs — for example, Ohio is generally low, and Ohio is often seen as a place that auto jobs ultimately left. Hm. I also wonder what this means about migration — NC, which has two big cities in it among the bottom 10 here, was also one of the highest population increase states of 2013 (I remember seeing that somewhere). Are people flooding the zone on a place where they can’t achieve big? Or is the right way to view this as contextual to each situation (i.e. the job you’d be moving for, etc.)? Regardless, it’s fairly interesting.

Here’s a bit more on the study and its context, including this money quote:

“The U.S. is better described as a collection of societies,” the researchers write, “some of which are ‘lands of opportunity’ with high rates of mobility across generations, and others in which few children escape poverty.”

And here’s a broader breakdown, from The New Yorker:

The obvious interpretation is that it is good news. Despite the enormous increase in income inequality that the work of Saez and many others has detailed, Americans in their twenties and thirties still have about as much chance of making good as their parents did a generation ago, regardless of where they come from or how rich their families were. Indeed, the study suggests that, for the most recent cohorts, social mobility may have increased slightly—at least as far as college attendance is concerned: “Children born to the highest-income families in 1984 were 74.5 percentage points more likely to attend college than those from the lowest-income families. The corresponding gap for children born in 1993 is 69.2 percentage points.”

Now for the bad news: the Horatio Alger myth is still a myth. Relative to many other advanced countries, the United States remains a highly stratified society, and most poor kids still have few prospects of making big strides. I’ve already mentioned the finding that the odds of a child moving from the bottom fifth of the income distribution to the top fifth are less than one in ten, and have been that way for decades. For children who are born in the second fifth of the income distribution, those who might be categorized as working class or lower-middle class, the probability of moving up to the top quintile has fallen significantly. For someone born in 1971, it was 17.7 per cent; for someone born in 1986, it was 13.8 per cent.

Well, Texas does not fair as well as you report. Its mainly the more white suburban counties with the exception of Fort Bend which has a lot of middle class minorities. Houston and Dallas do worst than Los Angeles-Orange County and San Diego. In fact there is all this cost of living that made La high poverty but the study shows LA still outpefroms the major metro areas of Texas on social mobility. In fact many people would bet better if they stay put in Minnesota than run to Texas or the rest of the south..

“I live in Minneapolis and can’t fully explain why it always makes these lists. It’s a great city with good Fortune 500 companies, but it’s very hard for an outsider there; the culture is super insular — but maybe that contributes to the absolute upward mobility too”

I think you’re right, the insularity contributes to people getting ahead here in the Twin Cities. Those who never leave are offered opportunities that newcomers aren’t, whether or not they’re actually qualified for said positions.