Religion and politics have been tied up together for centuries, so I’m not going to attempt to talk broadly about that (there are entire departments at well-regarded universities who study these types of topics). Rather, there’s a short, but interesting article on The Atlantic right now about a voting bloc no one really pays attention to: those that classify themselves as “spiritual” but not necessarily “religious.” I would actually throw myself in here. I believe pretty strongly in God, an order to the universe, and most of the Bible and religious teachings. I also almost never go to church sans weddings and funerals. I don’t tend to vote along strictly religious lines.

The story goes like this: 2012 was perhaps the end of evangelical dominance in politics, as 79 percent of evangelicals voted for Romney — and evangelicals were responsible for 27 percent of the overall electorate — and yet, Romney still got trounced. The conventional motif is the rise of the Latino vote, which should be an even bigger factor in future national elections. But maybe there’s something else to consider (aside, of course, from wind energy in Iowa). Check out these numbers via The Atlantic:

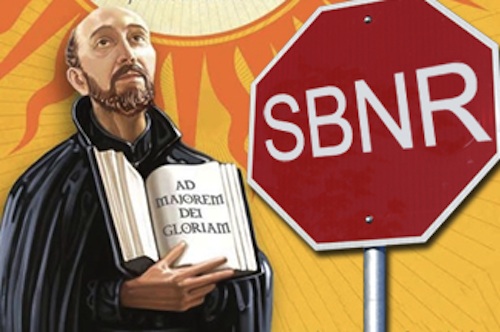

A fifth of Americans check “none” on surveys of religious preference. Among the young adults under 30 who helped propel Obama into office, a full third check “none.” Atheist pundits are quick to claim these gains for their own, but that is not the case—nearly 70 percent of “nones” report belief in God or a universal spirit, and 37 percent describe themselves as “spiritual but not religious.” This may or may not be the story of the decline of “religion,” but it is clearly also the story of the ascent of “spirituality.”

Look at the end there — 37 percent describe themselves as “spiritual but not religious,” but they’re not necessarily atheists. If you can capture a sizable portion of this bloc and propel them to the booth, you’re about 1/2 to 3/4 of the way to the Presidency (or your Congressional district). But what does it all mean?

Religiously unaffiliated voters are strongly Democratic in national elections, and a majority are socially progressive on issues such as abortion and same-sex marriage. But there is growth possibility for Democrats. While religious nonaffiliation has expanded rapidly in recent years, “nones” account for a flat 12 percent of voters in presidential contests since 2008. Over the same period, the percentage of “nones” identifying as Democrats fell slightly, while the percentage identifying as independents increased to half—good news for Republicans and third-party candidates. Republicans are unlikely to wring much from spiritual voters; but Democrats stand to gain significantly, or lose out, depending on their ability to inspire them.

So … Democrats are a bit more confident in the future of America, and the gap between Democrats and Republicans is getting progressively wider each year. Swing districts basically don’t exist anymore. In 2014, it looks like the big issues will be inequality, ObamaCare, jobs/economy, and potentially guns/security/privacy. All those issues have pretty linear liberal and conservative lines (inequality and the economy are maybe a bit muddled, but not much), so any races in tighter districts (there are roughly 34 of them) will come down to a series of trend lines that are best understood locally. These trend lines are obviously going to be different in a place like Washington state and NE Kansas, but finding ways to reach this “spiritual but not religious” group could be a big play for politicians. As for 2016, it’s nearly impossible to predict what the key issue driving that election will be — personally I think if you see a lot of 22 year-olds entering the world with no real possibility, you could get another Obama “tide of change” candidate rolling up and stealing Hilary’s thunder (“second verse, same as the first, little bit louder and a whole lot worse…”). But no one knows and that’s pointless to try and predict.

So how can a candidate reach out to this 37 percent bloc? First, start with this assumption/assertion:

But in the last several years, sociologists and other religion scholars have begun to take spirituality more seriously, and to think more expansively about its social and civic manifestations. Some of us are finding that “spiritual but not religious” people usually do care, and deeply, about community and civic participation.

Alright, so they do care. How does one get them to vote for a specific candidate? Again, from The Atlantic:

If the social project for spiritual people is to identify forms of community and civic participation with which they feel at home, then politicians have the opportunity to be partners from the inside, to help to shape these community and civic forms.

This includes, first and foremost, strategies of listening—polling, interviewing, researching—to understand not just how spiritual people vote but also the ways in which their relationships with the sacred open out into their civil involvements and political decisions. (Journalists and scholars need to become better listeners, too.) It includes strategies of speaking—of shaping political language inclusive of “spiritual but not religious” people rather than lumping them in with non-believers. Obama was the first U.S. president to acknowledge non-believers in his inaugural address—America, Obama said, is a “patchwork” of “Christians and Muslims, Jews and Hindus, and non-believers.” That was a step in the right direction, but the truth is that “non-believers” describes only a fraction of Americans who don’t identify with a religion. And it includes strategies of action—of setting policy agendas that emerge from this conversation. Such policy may look much like what pollsters already tell us the “nones” prefer. But in the context of intentional listening and speaking it will seem less jaded, more apt to come to fruition, and more inspiring of spiritual voters to show up at the polls.

That’s a bit vague — it doesn’t talk about specific campaign promises to make or say “avoid talking about guns” — but it goes back to the central idea of listening, which politics should be rooted in anyway. It also speaks to acknowledging non-believers, which might be tough for a candidate worried about alienating a strongly Christian base (or another denomination). Regardless, the trend line is there — if 2008 was about youth and 2012 was about minority outreach, 2016 could be about those who believe but aren’t necessarily connected to a specific faith or church. A message that can reach those — perhaps something about reinventing cities as civic hubs — could be the kingmaker.

As much as I enjoy a thoughtful article like yours, and as much as I deeply want to believe otherwise, I no longer think most people vote based on issues. Coming across with ease on-camera trumps the rest of the message by a considerable margin. Heck, 75% of the time whichever candidate is TALLER wins! Mrs. Clinton may want to consider leg-lengthening surgery.

The increase in the number of non-religious (but spiritual) here does mirror that trend in Europe. Somewhere along the line people have begun to figure out that you can be ethical and involved in social justice causes without joining a church.

I’m sorry, but this comment isn’t going to be useful to most:

Sans is French for without. It’s also used in other terms like sans-serif (no serifs on letters in a font)

Saying sans weddings doesn’t make sense, however saying save or except for or with the exception of works just fine.

I guess I’m mad at the hipster language…

The word sans was used I correctly. Sans is French for without. It is also used in terms like “sans-serif” meaning that a particular font doesn’t have a serif.

I guess I’m sort of mad at the hipster version of the word which is pronounced sanz instead of “sah” which is correct.

One of the big challenges as I see it are the terms we use. Works like atheist, god, or religion tend to be anti-productive to conversations that are inclusive. Many people will instantly turn off when they hear them.

Regarding the “spiritual but not religious” moniker, it is gaining in popularity, but there’s currently not much for people to rally around. Humanism tells people they can be “Good Without God” but many choose to focus on the “Without God” rather than the “Good”.

Finding a way to rally and unite people around the “Good” and motivate them to act is key to building a movement that can serve as an antidote to the cynicism and malaise that permeates much of our society.

Like Louis C.K. said, “Everything’s amazing and nobody’s happy.” Find a way to get people to believe in themselves, each other, and our society again, and the politics will follow.