In my first year of graduate school, I tried to set up a series of events with business leaders from the Minneapolis area. The basic idea would be: at a bar, appetizers and drinks, a business leader speaks for five minutes on “The Biggest Failure Of My Life … And What I Learned.” (I would have allowed flexibility in topic, although not really in time — I wanted these things to be short and punchy, with the focus on one critical lesson and networking opportunities.) For a variety of reasons, not the least of which was my own laziness, this series never really got off the ground. But I’m still intrigued by the idea of talking about failure as a part of the work experience.

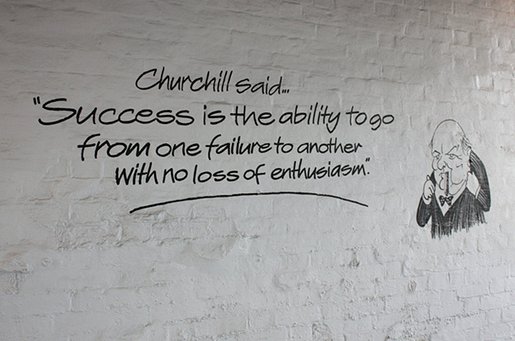

It’s undeniable that failure is an essential, active part of your life. You lose deals, relationships splinter, you set goals and don’t meet them. This happens to everyone. It’s a pre-requisite for being human in many respects. The New York Times talks about it, bloggers talk about it, management magazines talk about it, and TED talks about it:

Let’s stop for a second and admit one thing: in the Silicon Valley / Bay Area culture, failure is often embraced. In fact, paradoxically in those working environments, it is often thought of like this: If you’re not failing, or you haven’t failed, you’re probably not innovating enough.

It’s probably not a coincidence that some of the realest wealth in America currently resides in that area, but more on that in a second.

I’ve worked at a few different places — Teach for America, ESPN, PBS, University of Minnesota and now a travel company. Those are all very different types of organizations and structured very differently, but … one crucial thing they have in common is that people very rarely discuss the idea of failure.

None of those are Silicon Valley companies, of course.

I do find this interesting, though: there’s a business mantra that “Failure is not an option.” In fact, a couple of weeks ago at a staff meeting, I saw someone I work with writing on a legal pad: “Is how or why more important?” I would almost always say why is more important, even though I know nothing of the context of what she was writing — but I almost feel like “how?” isn’t even a question in business anymore. If someone tells you something needs to be done, the assumption is that it will get done — it’s not a question of how so much as a question of when for most projects (and that leads to rushed, bullshit results — but that’s for another post on another day).

But failure is everywhere. It happens around the world literally every second. It probably happens somewhere in your organization literally every 1-5 minutes. But in 12-13 years of working, I’ve only a handful of times sat down in a meeting and had people actively discuss failure, learning from failure, moving forward from failure, etc.

Isn’t it weird that we don’t discuss something that happens all the time?

Part of this may be part of the broader disconnect in the world of business: there’s really no focus on learning. The true value for most people in a business is “What you know” or “Who you know,” not “How you go about the process of knowing.” To talk about failure would involve a heady dose of talking about learning — how you rebound from mistakes, etc. I don’t think people are really comfortable with those types of discussions; they’d almost rather spend time in meetings discussing what they already know.

One advantage for me to talking more openly about failure would be this, though: you’d reduce the disconnect between “the haves” (the top levels) and “the have-nots” (the foot soldiers). Oftentimes, people respect hierarchy straight up on face. “This person is my boss, or my friend’s boss, so they must know better than me.” But what if you learned that managers in your company had frequently made mistakes, including some huge mistakes involving money? Wouldn’t that make you feel better about your own trajectory, and wouldn’t it make them seem more human? I feel like that could organically break down some of the communication problems you see at work.

To talk about failure inherently implies being vulnerable. When you’re vulnerable or transparent, you’re opening up more opportunities for connection. I see that with this blog all the time. When I write pretty transparent, vulnerable things — like this or this — I tend to get more views, comments, shares, e-mails, and the like. When I write something more generic, that happens less so.

I know the human brain probably isn’t set up to spend a lot of time discussing failure, and that’s fine. I’m not advocating that a company should dedicate a lot of resources to this — that would be absurd, and negative, and very little would ever get done aside from discussing failure (which would seem more like psychotherapy than work) — but I feel like once a week, or twice a month, or something of that nature would be good.

Think about it this way: organizations often talk about transparency and communication and wanting more of it, but how often do they actually do anything that would promote that? This is a really simple way to achieve that goal — just talk about failure here and there. Talk about what happened, why it happened, and what you learn. Expose yourself and your flaws. It can do wonders.

Reblogged this on Gr8fullsoul.

We had a failed project this year and have put quite a bit of effort into learning as much as we can from it. Our own failings, the failings of the client and the failings of the supplier (since in most the projects we work on there are multiple parties). After having read this, it’s made me want to formalise the learning more – you know, write it down and stick it up on the wall kind of thing. Adding that to the list of things to do now…