Currently I’m sitting at a WeWork near some guy doing smile-and-dial for his either insurance or title company business — it probably doesn’t say much about his cold call ability that I can’t tell what he does, even though I can hear his side of the conversation — and at some point, he told Siri to call his wife. Siri instead called someone named Bart, and this guy got very mad at his phone. I was getting bored and frustrated with Mr. Smile and Dial, so I started reading this article on “controlling emotional contagion” and probably got a little more frustrated. Consider this paragraph:

As a leader, controlling emotional contagion, especially during the pandemic, should be a priority. Ignoring the power of mood, whether it originates in the self or is “caught” through contact with others, means losing an important opportunity to influence outcomes. Cognition and emotion are completely intertwined: If you and your team are stressed, fearful, or worried, your decision-making and ability to process information are negatively affected. Conversely, positive emotions lead to better employee attitudes, creativity, and job performance.

Almost everyone on the planet who has been a manager knows all this stuff. It’s common sense at some level. And yet, most managers don’t do it and sometimes do the polar opposite. So what gives?

What do managers think is “integral?”

Back in June 2019 (I was broke as fuck then), I wrote this thing about telling managers that “emotions were integral to work.” No doubt. We’re emotional creatures. Obviously we have emotional reactions to things at work, because work is also very tied to self-worth and relevance for a lot of people. If someone dresses you down at work, it’s gonna sting, and there will be an emotional reaction. If someone elevates you at work or you’re getting poached by a rival, that’s gonna feel good. This is life, right?

But managers, despite clearly knowing this — and often having emotions themselves — don’t behave this way with direct reports that often. If anything, they’re more “absentee” than worried about “emotional contagion.”

So, why?

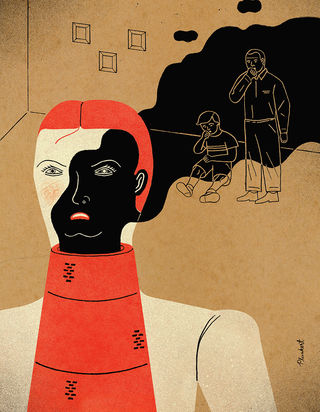

This answer shouldn’t be too confusing: first of all, days are limited. There is a finite amount of time. You may be getting pinged by your spouse, your kids, your boss, and your direct reports. How would you prioritize that list? For most people, the pings from the direct reports are at the very bottom, and with good reason. So that’s one thing.

Second thing is general perceptions of work. A lot of people who rise high in organizations view work in very black-and-white, brute-force terms. It’s about hustling, deals, late nights, slaving away, etc. It’s not about emotions and moods. That feels like fluffy shit that Gen Z demands. Forget those punk kids.

Third thing is that a lot of managers are overwhelmed by their responsibilities, don’t want to admit it (for fear of getting fired or demoted), and they spend all their time managing up because it feels like a smarter thing to do long-run.

Fourth thing is that a lot of managers just sit in meetings and answer emails all day, and humanity is essentially stripped from their role, and then they get scared about how they might get automated out even though that’s the perfect end function for a manager that doesn’t care about people. Ain’t life amazing?

So those are kinda the big reasons.

Could we make managers care more about emotions and moods?

Broadly, no. But if you want to try, you need some incentive structure around it. I don’t know the answer but the best thought I’ve had on it recently is that managerial compensation and incentives needs to be tied to:

- KPI delivery (standard)

- Reviews from senior leadership (standard)

- Reviews from your employees (done at some places, new wrinkle at others)

- How many of your people are promoted or advanced (Home Depot does this for store managers)

You can’t tell Marty Middle Manager that his bonus is contingent on “controlling emotional contagion,” because he’ll laugh in your face and potentially quit. That’s not a “work” thing to a lot of people, as mentioned above. But you can tell Marty that his employees are now reviewing him, and advancement of his employees can get him more scratch, and that might make Marty care more about moods and emotions and actually working with humans instead of emails and standups.

That’s my idea. If you want to take a harried, middle-aged person with multiple responsibilities to their family, friends (ha, who has time?) and bosses and you want them to care about “emotional contagion,” you better give ’em incentives to match that need. Right?