I’ve had a bunch of job interviews in the past two months or so, and whenever we get to the “What do you want in a corporate culture?” question, I usually mention the idea of a place where not everyone runs around talking about how busy they are. Since such a place may not exist in the modern era, that probably costs me a few jobs here and there, but I stand by the idea. We’ve created an entire sub-culture around being busy, which is funny/ironic/interesting/your word choice because how busy you are is ultimately your choice, meaning you have some measure of control over how to approach it. Phrased in a more academic way, it’s “the undisciplined pursuit of more.” Harvard Business Review has a good article about this up right now, including this quote:

This bubble is being enabled by an unholy alliance between three powerful trends: smart phones, social media, and extreme consumerism. The result is not just information overload, but opinion overload. We are more aware than at any time in history of what everyone else is doing and, therefore, what we “should” be doing. In the process, we have been sold a bill of goods: that success means being supermen and superwomen who can get it all done. Of course, we back-door-brag about being busy: it’s code for being successful and important.

Sometimes I think blaming the culture of everyone-must-be-busy on social media and Smart Phones is akin to blaming any school shooter on violent video games — it’s almost too easy. But … there is a kernel of truth there. Last night I went for some drinks with my wife and a friend, and at every table around us at one point, we saw that each member of those tables was on a SmartPhone (no actual engagement with the people they were with). You’ve probably seen this too, at bars/restaurants/public places. People get taken away by their screens and even if what’s on there isn’t making them busy, they construe it as such.

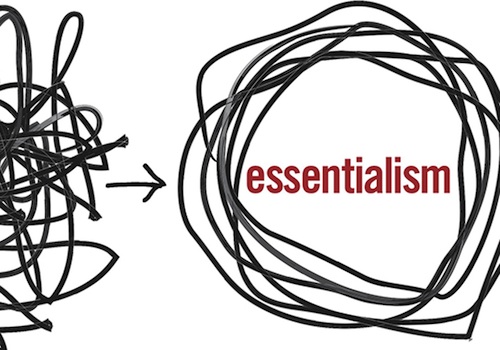

The HBR article goes on to talk about this idea that from the culture of being busy could spring a movement around “Essentials.” Those would be people who fix their work schedules to focus on getting productive things done, as opposed to sitting in meetings; they would be people who take time out to think about broader strategy and ideas instead of always being in the moment of what has to be achieved next. Ideally, all C-Suite level people should be Essentialists — you work hard, you get rewarded, and now you can take a bigger-picture view (and have more of a family focus). Unfortunately, it doesn’t always work that way (C-Suite means more responsibility and more ties to things if they fall apart, which can mean way more screen time). This is all closely tied to mindfulness, which apparently was a big focus at Davos this year.

I like the idea of “the disciplined pursuit of less,” but I also think it’s but a pipe dream for everyone except about 7-10 percent of the population. I’ve worked in a lot of different places — a public school, some Fortune 500 companies, a major research university — and in every place, I’ve seen a similar characteristic among most people at a job. People usually take any manager’s viewpoint on something at complete face value — i.e. “This is now a priority that must be finished today.” That’s good in one sense; you should follow what your manager says. The problem is: for managers, especially new managers, everything is a priority because they’re trying to excel too. This exerts downward pressure, which, as we know, bursts pipes (or employee engagement). The only way a person can get after a “disciplined pursuit of less” is to understand what matters now, what matters tomorrow, what matters next week, and what matters in a month. In other words, when someone is telling you that everything must be done now, you need to be able to parse out context and understand that not everything is due this second. Without that context, everyone just becomes rats on a wheel to the 82 percent of bad managers in our global workforce.

I was on teams in graduate school where a paper/presentation would be 15 days away, and they’d want to meet every 1-2 days in the interim to “make sure we were aligned;” often, the meetings would contain virtually no new information. I tried to switch it to two meetings across the two weeks before the deliverable, and people told me “I wasn’t taking it seriously” (FYI, it was 30 percent of our grade, not something like 80 percent). I’ve also worked with similar people. You can pursue less, yes, but it requires three essential things: context, choice, and the ability to be OK with not being as busy (thus going against what you’re hearing from everyone else). If you can master those three aspects, you can do all this.

Disciplined pursuit of less – fantastic!