Harsh truth about any type of business school/business education: you will have a lot of breathless conversations about SWOTs and case studies and all that. People especially love to analyze why a company failed — and a big one that comes up a lot is Blockbuster (Kodak is the other, I’d argue). People want to assign it to any number of core work virtues they assume are important, like “They were behind the times on innovation!” or “They didn’t protect their margins!” I had a Saturday morning class at business school where all we did was SWOTs and have conversations like this. It was a 12-week class. At Week 4, I wanted to bash my skull in. At Week 8, I stopped going. I still got a B-Plus. You could make an argument that I should have tried harder, and you’re probably right. But you know what? At this moment I’m all good with not caring.

Here’s an article — by the Digital Tonto guy! — that goes into a deeper explanation of the actual reasons why Blockbuster failed, and it turns out it’s a lot simpler than anything we want to assign it to:

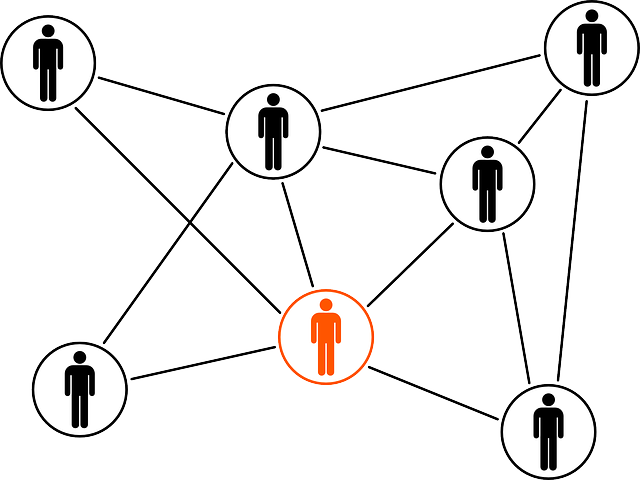

In the Blockbuster case, a successful CEO was faced with a disruptive threat and came up with a successful market strategy. However, because the networks within his organization (e.g. franchisees and investors as well as, to a lesser extent, internal operations people), the plan failed.

McChrystal, on the other hand, focused on creating a shared purpose among his internal networks and the strategy took care of itself. In effect the structure, rather than the plan, was the strategy.

We talk about “purpose” all the time in the modern working world — well, at least thought leaders do — even though companies can’t define it and it’s damn near impossible to achieve. Most people don’t get the concept of purpose because it’s not tied to the bottom line, at least in any kind of direct way.

But … the ideas here are important.

If you create a shared purpose among your internal networks — so basically, you get buy-in and communicate well internally and align people to the same goals — then the strategy takes care of itself. The structure becomes the strategy, as opposed to the plan!

That’s actually good for a lot of people in business, since no one really knows the difference between “operations” and “strategy” anyway.

Here’s the rub, then: you need a culture because that culture can create alignment, and when you have alignment around goals, then your good ideas — your “strategy!” — can get through, and your bad ideas will get filtered out.

You basically need to create a networked culture around alignment and goals, and the rest of the stuff (strategy, operations, purpose, margins, revenue, anything else you may be chasing) will ultimately fall into place.

Not extremely hard, is it?