Even though no one seems to understand their success with living, breathing people — instead attributing it to cash or hand or KPIs or margins or some other BS — Google has long been one of the ‘best places to work’ and is often lauded for how it deals with employees. They’ve got this new ReWork site — which is partially helping to promote the book of their HR head, Laszlo Bock — and one cool aspect of the site is that they give some insights into their processes.

Despite what a lot of executives at companies think, people issues are important. Your products and services make you money, yes. Your processes allow for that money to be funneled in properly and keep the rank-and-file at bay from the big dogs, yes. But people work on the things that make you money, from production to marketing to PR to IT to whatever else, so you need to understand how to treat employees the same way you treat customers. Most high-level people in organizations don’t understand this, and instead run around screaming breathlessly about revenue forecasts. That’s life.

Here’s another potential tipping point in the next 15-20 years of work, right? Some companies are going to start competing on the idea of People Analytics. That’s a fraught concept in some ways — people are creatures of emotion, so trying to corral them into the right companies with a logical process is hard — but when companies do it right, it’s going to be a huge competitive advantage for them. Imagine getting the right people for your culture? Then organizing them on the right teams? Seems like a pipe dream, but if you hit those targets about people — instead of some Q3 revenue projection thing — you’ll be light years ahead of some of your competitors. Eventually, “the gut feel of the execs” model needs to fade away and give way to “We know what makes a person successful in this organization and this team, so let’s get that type of person.”

But what does make a team successful?

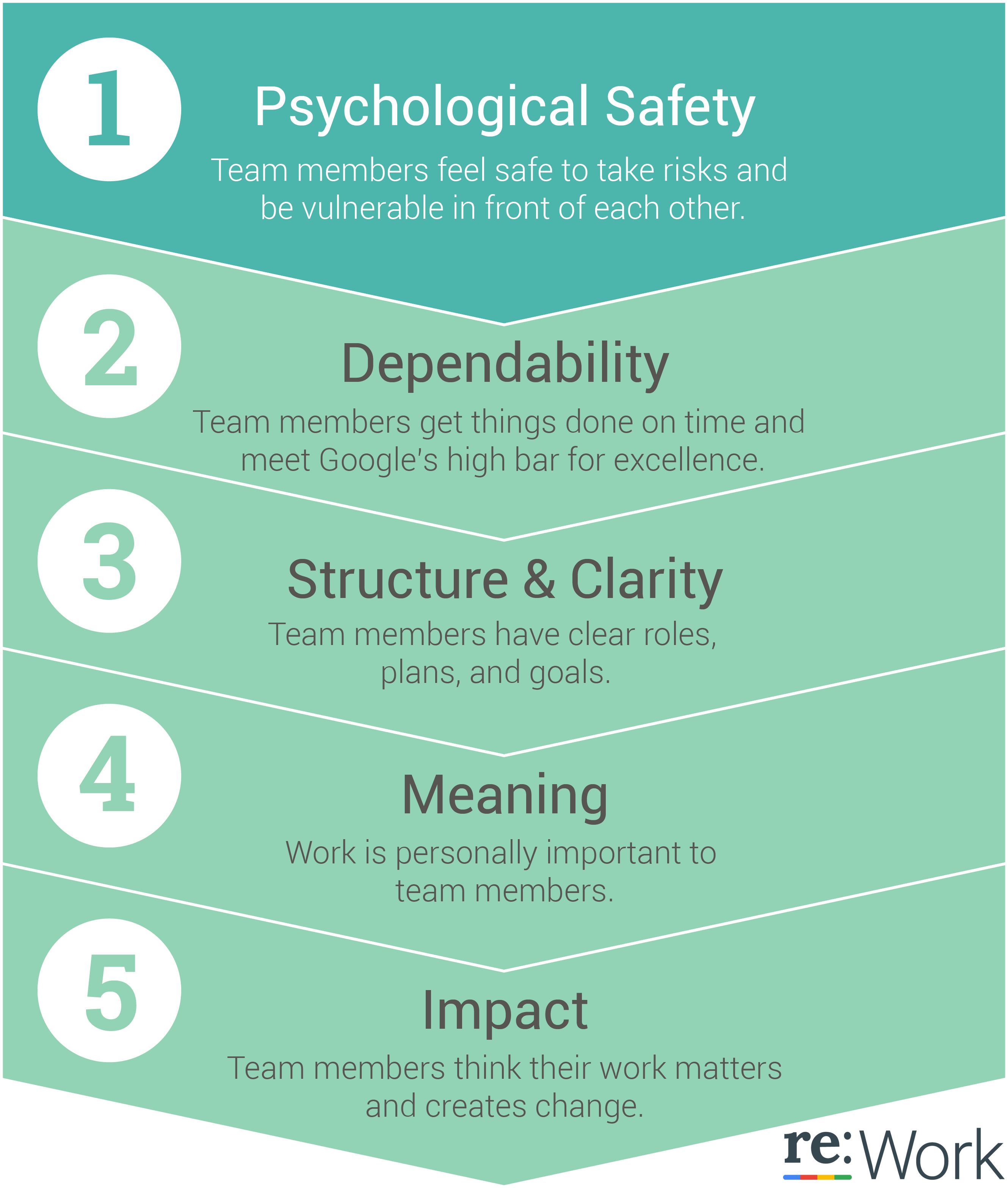

Here’s Google’s visual representation of it, based off this post:

So you’ve got five key factors:

- Psychological safety

- Dependability

- Structure and clarity

- Meaning

- Impact

By far the most important one is the top one — psychological safety. Here’s why, via Google:

But remember the last time you were working on a project. Did you feel like you could ask what the goal was without the risk of sounding like you’re the only one out of the loop? Or did you opt for continuing without clarifying anything, in order to avoid being perceived as someone who is unaware?

Turns out, we’re all reluctant to engage in behaviors that could negatively influence how others perceive our competence, awareness, and positivity. Although this kind of self-protection is a natural strategy in the workplace, it is detrimental to effective teamwork. On the flip side, the safer team members feel with one another, the more likely they are to admit mistakes, to partner, and to take on new roles. And it affects pretty much every important dimension we look at for employees. Individuals on teams with higher psychological safety are less likely to leave Google, they’re more likely to harness the power of diverse ideas from their teammates, they bring in more revenue, and they’re rated as effective twice as often by executives.

Completely logical. It rolls up with Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs, which you’re probably familiar with.

Around Nos. 3-5, it starts to get harder — many people lack structure and clarity around their work, and many (especially at lower levels) lack meaning and impact.

Let’s bring in another important article, recently published on Harvard Business Review, about employee engagement. Pay attention to this specific section:

Let’s start with what doesn’t work. Incentives or other extrinsic rewards—individual bonus schemes, promises of nice offices and titles, and other tangible benefits—create transactional relationships, not deep bonds to an employer. Indeed there is a good deal of evidence that using such individual incentives actually creates self-interest, lowers trust, results in poor teamwork, and diminishes commitment.

That part is really important. A lot of bosses — and bosses are notoriously bad at understanding motivation — assume that the No. 1 thing for everyone is salary. Yes and no. Salary is important, but look above: it creates a transactional relationship. If you’re only hitting targets for your salary, that’s good for your company — and if you have a nice salary, it’s good for you — but that’s not an actual bond. There has to be some meaning, purpose, etc. behind the work. That’s what Google is saying above.

There’s another managerial flaw here. Look, not every position in a company is a revenue-generating one; heck, 4 in 5 probably are not. If the only thing that managers understand is “making money” and “where’s my annual bonus?” then they probably have no idea how to communicate anything back down a chain. If you manage a non-revenue employee and the only motivational structure you understand is money/revenue/bonuses, you have no idea how to tell that employee why their work matters to begin with. That actively creates disengagement. That’s happened to me in 4-5 jobs I’ve had, probably.

Other models to consider about putting together good teams include:

- C-Factor: Namely, how curious are the people on your team?

- Overlapping productivity styles: All one type and the team will accomplish nothing; a mix is good.

- Self-awareness: Hard as hell to measure/quantify, yes, but very important.

This all comes together with another thing we often misunderstand: in reality, there’s no such thing as a “bad employee.” There are “below-average employees in bad fits,” yes. But an employee is a function of many things, from their own intelligence/curiosity/skill set to their manager’s to their manager’s ability to define priorities to the overall culture of the organization. You could say the same thing about “great employees;” sometimes people leave one organization where everyone hated them, then they go to another and they’re a superstar. The organizations might be in the same industry. So how was the same person so bad at one place and so good at another?

Simple. Cultural fit, and the relevance of the work, the structure of the team he/she was on, etc.

This is what we miss when we breathlessly run around from meeting to meeting to e-mail to e-mail to standup to standup to scrum to scrum to task to project to deliverable (oh my!). Work is about processes, yes, and we try to apply logic to it, yes. But work is composed of people, and people have feelings and emotions and fit together in different ways — and until we make an actual attempt to understand the best ways to maximize that in our own organizations, all we’re all doing is failing upward.

Dear Ted –

We have a lot of interests common you and I… and probably a similar outlook on many issues. I’ve been putting together a blog on more or less these themes for the last 6 months…but I’m slow! I’m particularly interested in our modern relationship with our working lives, which for me is characterised by a global pandemic of disengagement (a global survey in 2011 reported that only 13% of employees felt engaged with their work).

What is desperately needed, and frankly long overdue, is a reinvention of work to be a place where people find identify, meaning, purpose, self-confidence, affection and companionship. Why is it that is has become the accepted norm that we ‘check ourselves out’ when entering our places of work and don’t show up with our whole selves: our head, heart, hands and guts, but instead put on ‘professional’ masks’ reserving our authentic selves for our family & personal lives? I found a beautiful but disturbing quote from an authentic leadership coaching organisation, by the name of Tenemos, which certainly resonates with my feeling about many of the places I’ve worked in:

“The most painful experience of modern man is that nobody really knows us, and nobody seems to be particularly interested. To avoid feeling that pain, we avoid disclosing ourselves in day-to-day life. We behave in a way that results in a staggering loss of human potential and the resulting economic value. In our workplaces, we do not dare to show our true and whole self. We do not feel welcome, and co-create work environments where sub-optimal results and shared ineffectiveness are normal. Although we hunger for being seen, our need for safety makes it impossible for anyone to authentically connect with us. True effectiveness is very radical, scary, terrifying – nothing anyone would want per se. We avoid it at all costs. Temenos provides a safe setting to explore this space to develop our existing skills. We discover that we can open up to people and learn that this satisfies a deeply rooted human need. With this experience, we may dare to treat each other more openly, truthfully, and effectively than before. We’re more aware of who we are, and what we want. “

Speaking of safety, I applaud Google for that ‘psychological safety’, you wouldn’t think it would be an issue in with teams of presumably super-bright, confident players… much it just goes to show we are all human and as leaders we must model the way and admit our own self-doubts and vulnerabilities to encourage trust building. I’ve just applied for a role which had the accountability “Building a trusting and safe environment where problems can be raised without fear of blame, retribution, or being judged, with an emphasis of healing and problem solving. Facilitating getting the work done without coercion, assigning, or dictating the work.”. So that sounded like the kind of organisational culture I could thrive in. AndI agree with you people first, then principles. then processes, then tools. And people of course are messy, squidgy and emotionally & cognitively irrational, not to say entirely screwed up. It’s not only a the wrong employee in the wrong organisation – which from my own personal experience for example ‘culture’ is going to be crucial as to whether I thrive of despise an assignment (but a tricky one to assess in t an interview session or the few minutes you have walking round the building…and don’t think you can really send a culture questionnaire in before accepting the role). But in fact its right role in the right organisation, on the right project, with the right boss, with the right guy sitting next to you who’s doesn’t really grate on your soul.. and a day when you haven’t had a blazing row with your girlfriend and generally feeling on form. These are variables that determine whether your a good employee at particular moment

In response about your point about making a difference: I do think that most companies realise not everyone is destined to make an impact on the bottom line. Indeed it may be a very few who during their career do: I read recently that 93% of newly launched packaged consumer goods fail to make a profit and are with drawn within 3 years in the US. So in these contexts you really have to satisfy yourself ( and I think it’s a feature of many successful businesses that they do) that there is a particularly powerful return investment in participating in financially failed projects: and that is learning what NOT todo next time.

My job as an Agile Coach involves trying to grow self-organising (at least over the who and how they organise their work), small, cross-functional teams by developing skills such as collective decision making, problem solving, co-creation, non-judgmental listening and even self awareness which I agree is the corner-stone of all self-mastery – tricky to measure but not too difficult to develop using techniques like mindfulness and deep-listening.

Of course I’m dealing typically with young, cynical IT types but when they get that they are being offered (and it is only offered sadly – they have no right to it) the opportunity of autonomy over being told what to do through hierarchical command and control, it scary for them, but generally they step up to the responsibility and I seek to gain their respect through appealing to their down-to-earth, common sense, self-interest, sprinkled with a little bit of aspirational fairy dust about the magical, mysterious transformative powers of agile that I, the great Agile Guru will teach them provided they follow in my footsteps unquestioningly every step of the way. (Only joking on this last point see my post of the perils of the boot camp approach to teaching agile.)

But this is where I get my biggest kick: being an enabler of individual and team growth – growth in self-mastery and self-belief that enables autonomy and often a transformational shift in enjoyment, motivation and commitment to the work they do. By providing supported empowerment, along with self-organisation skills and a strong sense of a collective common purpose I’ve witnessed the transformation of teams to really astonishing levels of trust, intimacy, affection, creativity, energy and passion.

My instinctive leadership style is participatory which means I try to facilitate the team into what I call a ‘flow-state’ where their ideas will build, one on top of the another, and through leveraging the diversity of perspectives in a positive way their collective genius generates a solution, a statement of needs, a plan, a decision that is far superior to anything that anyone one of us could have come up with by ourselves. Somehow it’s about enabling an outcome from the ‘whole’ that is greater than the sum of parts.

In fact I’ve recently decided to adopt the term ‘Collaborative Leader’ so I’m not so tied to the to my skill-base of facilitating group process, mentoring, coaching and mediating but can also can apply myself to developing collaborative partnership’s between groups, departments and organisations. That’ll certainly stretch my powers of empathy, patience, tenacity and coalition building to the limit!

Of course when you empower one group – in my case typically moving decision making down to where its is most effectively exercised, you disempower at another level. While some manager’s are secure enough to cope with this and are happy to share control, others resist, fearing a loss of control, power and status. So I have to work hard at getting the supportive stakeholders on side to counter the tacit or open resistance of some layers of middle management. I can make enemies in powerful places and ultimately it’s the broader organisational culture and will of the executive team that determines my success.

Now I’ve just been reading about this new school of dialogic OD, which you probably know, is a post-modern revision of diagnostic ’planned’ OD. And I discovered when I bought the book that all my favourite Change Models from Theory U. to the Art of Hosting to Appreciative Inquiry were all dialogic. So can call myself a dialogic OD practitioner!

Like in software development they’ve realised they can’t directly control the outcome of change in a complex, adaptive system purely through controlling interventions. So the method is broadly to create a disruptive space where traditional habits and socially constructed meaning are challenged, which puts people into kind of chaos mode and forces them to engage in new organisational narratives that challenges old perspectives and generates new ideas and stories that are more adaptive in providing a basis for how people in the organisation find meaning. Sounds a bit tautological to me?! And you’d certainly have to have balls to walk into an organisation with such a fluid and open-ended process… but its fascinating the extent to which something as abstract as ‘Complex Adaptive Systems Theory’ has had such an tangible effect on business and organisational theory and practice.

But one thing it made me think about was: what are the cultural or organisational capacities which must be present, event in nascent form if a transformative agile OD programme is to stand a chance of being successful. Obviously I thought of Laloux’s three breakthroughs: self-management, wholeness and evolutionary purpose. But I don’t think I can expect those qualities in more than 5% of UKPlc so I want back and rediscovered Peter Senge’s Learning Organisation, and realised that his five disciplines were absolutely fundamental, and not only to the success of a change program. More significantly their experience or at least potential to become a Learning Organisation predicts whether they will thrive in the kind of emergent, uncertain product development, and continual learning and adapting culture of ‘being agile’, rather than just sleep-walking the processes and to ‘do agile’. Whole Systems Thinking, Personal Mastery. Questioning Entrenched Mental models. Building Shared Vision & Team learning. And he adds to this the recognition that people are agents, able to act upon the structures and systems of which they are a part. All the disciplines are, in this way, “concerned with a shift of mind from seeing parts to seeing wholes, from seeing people as helpless reactors to seeing them as active participants in shaping their reality, from reacting to the present to creating the future’ (Senge 1990: 69).

Not only does this describe the fundamental inside-out process which begins with hearts and minds but it also but it also gives us the qualities by which the change itself should be realised: Agile approaches are a means rather than and ends-in-themselves. They comprise a set of core values and principles, plus an extensive (and growing!) array of compatible practices that can help make the necessary mega-change from silo’ed, specialised organisations of the post industrial era to the robust, collaborative and cross-sectorial enterprises of the future.

But the agile transformation will likely fail if the coach/organisation applies traditional change management methods such as:

• top-down, using only a fraction of the intelligence and wisdom of the organisation

• big batch, so there is limited room for learning and adjustment along the way

• divisive: since big change is imposed, it is disruptive, and frequently counter-productive, it often leads to ongoing dissatisfaction and resentment among employees.

• hit-or-miss: if the big change doesn’t work as hoped it will take a lot of time and effort to organise the next attempt, and consequently

• infrequent, so staff are unpracticed in responding to change.

By contrast if we apply change using an Learning Organisation approach we shall likely succeed if change is:

• ubiquitous: everyone proposes as part of a ubiquitous, reflective and continual improvement orientated process of small action experiments.

• frequent: although everything isn’t in flux, small experiments are constantly going on

• incremental: small changes are the norm, and proposals for big changes are broken into smaller steps wherever possible, making for gentler change

• iterative: smalls steps that don’t work out can be re-done in different ways

• adaptive: it is possible to re-set goals mid-change in response to learning and/or new information, and

• familiar: since self-imposed change is going on all the time, when big changes do occur both people and teams are better-equipped to cope and respond positively and constructively.

All in all its made be consider than if an organisation is unfamiliar with continuous change my approach needs to be much more gradual and evolutionary to give people time to fully embody the shift in perspective and ‘engage the learning muscles’ and as they become more used to continual incremental change so we can accelerate. I’ll reflect more upon Senge’s theories in a later post because although he has been criticised for being overly idealistic about the appetite within capitalist organisations, where the bottom line is short-term profit, to be concerned with the long-term learning and development of employees, I suspect his ideas first articulated 25 years ago will be even more relevant 25 years from now.